Different views on Latino health care

Published 2:32 pm Tuesday, March 29, 2011

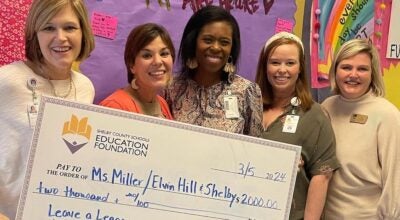

Though services through Community of Hope are provided free of charge and volunteer run, donations are accepted to help cover costs of providing the care. Prior to seeing the doctor on Sept. 30, patient Gilberto Barrientos, Helena, makes a donation to the organization while director Chris Monceret holds the box and administrative assistant Mandy Maldonado translates. (Reporter Photo/Jon Goering)

By NEAL WAGNER / City Editor

The lobby full of patients at the Shelby County Health Department in Pelham was filled with the echo of conversations in two languages when Community of Hope Executive Director Chris Monceret called for the group’s attention.

“God opened the doors for us to be able to do this, so we always open each clinic with a prayer,” Monceret announced.

Of the about 20 patients waiting in the lobby, about 60 percent of them were of Latino descent. Many of them did not understand the English words of the evening’s first prayer, but a quiet and reverent mood filled the building nonetheless.

The respectful mood continued as Community of Hope Administrative Assistant Mandy Maldonado repeated the prayer in the Hispanic patients’ native language.

After all eyes were open and all heads were raised, Montevallo resident Carmela Garcia silently walked to the small, white wooden box in Monceret’s hands and deposited a donation.

The Community of Hope, which is held at the Health Department every Thursday night, does not charge for medical services, nor does it require any donations. But for Garcia, it was about repaying a group of volunteers for changing her life.

The first time Garcia attended the clinic, she was taking several medications prescribed by a previous doctor. However, she said the medicines were doing nothing to cure her ailments.

“The doctors here helped me get education about the medicine I was taking,” Garcia said as Maldonado translated for her. “The medicines I was taking were not helping. They were hurting.

“They (the Community of Hope doctors) helped me get more education about the medicines I should be taking,” Garcia added.

“She said she feels a lot better now,” Maldonado added with a laugh.

Garcia, who originally heard about the clinic through a friend and was making her fourth visit March 24, is a native of Mexico, and moved to Montevallo eight years ago. Without Community of Hope, she said, she would have trouble keeping herself and her family healthy.

As was the case with Clanton resident Agustin Bolanos, who was also visiting the clinic for the fourth time March 24.

Bolanos, who was dressed in a pair of faded blue jeans, tennis shoes and a polo shirt, said he learned about the volunteer doctor-driven clinic when his wife came to the Health Department for a checkup.

“It is a big help for me, because I don’t make a lot of money. It is expensive for me to see the doctor,” said Bolanos, who was born in Mexico and recently moved from Shelby County to Clanton.

“It is a great help that I can come here and get medical attention,” he added.

A different medical culture

Almost every Thursday night for the past 13 months, Maldonado has been helping the volunteer nurses and doctors at the Community of Hope clinic scale much more than just a language barrier.

Maldonado is one of the few bilingual interpreters at the clinic certified to translate medical issues between doctors and Latino patients.

“I studied Spanish in high school, so I was pretty fluent when I graduated there,” Maldonado said as volunteer nurses behind her sorted dozens of the clinic patients’ files. “After I started volunteering here, I took a class at Samford to certify me as a medical interpreter.

“It’s important to further your studies by becoming certified if you are going to be a medical interpreter,” Maldonado added. “It’s a learning experience just being here.”

Beyond the differences in language, many Latino people have a different view of medical science than people born in America.

“There are a lot of cultural differences. Many Hispanic people have different beliefs about medicine than we do,” Maldonado said. “Some believe in home remedies for certain things that, to us, would sound ridiculous.

“But they are just things that have been passed down through the generations, and they are hardcore about them,” Maldonado added.

Maldonado, whose husband is a native of Mexico, has experienced the cultural differences in medical beliefs firsthand.

“After I had my baby, my mother-in-law told me to walk up flights of stairs backwards, or basically my uterus would drop out,” Maldonado said, laughing.

A strained system

For clinics such as Community of Hope, serving those in need is a faith-based approach to helping people who may not otherwise be able to afford health care.

All doctors, nurses, interpreters and helpers work without pay and serve patients on a first-come, first-served basis. Patients are served regardless of race, age, gender or legal status in this country.

But for other health care establishments such as hospital emergency rooms or urgent care centers, undocumented Alabama residents are causing a strain on the state’s medical field, according to a member of the Shelby County legislative delegation.

State Rep. Jim McClendon, R-Springville, whose district covers eastern Shelby County, said illegal residents are causing higher health care costs for everyone in the state.

“There’s no question about it. If people can’t be financially responsible for their health care, that cost gets distributed to other users of the system,” said McClendon, who is chair of the House of Representatives’ Health Committee.

“I’m going to go out on a limb and say that most folks who are here illegally do not have comprehensive health insurance,” McClendon added.

Most of the state’s residents receive health insurance through their employers. But because most undocumented residents do not have steady jobs, most do not have health insurance, McClendon said.

The lack of health insurance coverage frequently drives undocumented immigrants to use emergency rooms or urgent care clinics as their primary health care providers.

Officials at Shelby Baptist Medical Center declined to comment about undocumented residents’ effect on the hospital’s emergency room.

“The majority of people of Latin descent who are here illegally use the ER as their primary health care provider,” McClendon said. “That is an extremely expensive way to get primary care, and it’s really an inappropriate use of the system.”

McClendon said he is heavily opposed to any future national health care changes aimed at covering undocumented immigrants.

“As soon as they get here, they are breaking the law,” McClendon said. “It’s hard to say that hard-working taxpayers should pay money to the federal government to support those who are breaking the law. That is not a good system.”