Life behind the bars

Published 11:13 am Monday, April 11, 2011

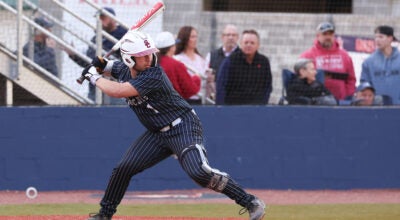

A corrections officer walks a couple of inmates down a hall at the Shelby County Jail. (Reporter Photo/Jon Goering)

By NEAL WAGNER / City Editor

Every day since March 10, Keith Shook’s day has begun the same way at the Shelby County Jail off McDow Road in Columbiana. At 5 a.m., Shook and his fellow inmates wake up and begin the same routine they completed the day before, and likely will complete the next day.

“Before I got on the work block, I would wake up at 5 and eat breakfast, go back to sleep until about 10, and then wake up and play cards until lunch at 12,” Shook said. “Then I would just watch TV and play cards until we ate again at 5.

“Watch more TV until lights out at 10. Go to sleep and wake up and do it all over again,” Shook added.

These days, Shook’s time in the jail has a little more variety, as he earned trusty status a few weeks into his sentence, and now completes labor inside and outside the jail nearly every day.

Shook, a 29-year-old Hueytown resident who has children ages 2 and 11, is serving a 45-day sentence for missing a pair of court dates in Pelham after he received a ticket for failing to wear a seat belt and driving without a license. He is scheduled to be released Easter Sunday.

Even though Shook previously served time in the Hueytown Jail and the Jefferson County Jail, he said he was apprehensive when he arrived to the Shelby County facility.

“I stayed to myself at first. But as long as you aren’t trying to scheme something up, you won’t get into any fights,” said Shook, who was dressed in yellow prison garb and was helping other trustys complete landscaping in front of the Sheriff’s Department.

“This is a very humbling experience. I don’t want to come back here,” he added. “These 45 days have taught me a lesson.”

Corrections Officer Lawrence works the controls at the control tower of Pod A at the Shelby County Jail on April 6. (Reporter Photo/Jon Goering)

An inmate peers into the hallway from behind the glass of a room in Pod A at the Shelby County Jail. (Reporter Photo/Jon Goering)

A separate society

Shelby County Corrections Division Cmdr. Stan Chapman approached a tan, solid steel door in the lobby of the Sheriff’s Department office and pressed a call button on a small, silver intercom mounted on the wall.

“Can I help you?” said the voice emitting from the speaker.

“Stan Chapman,” the commander answered, resulting in the high-pitched hissing sound of the door’s pneumatic lock disengaging.

As Chapman entered the doorway, the brightly lit, open environment of the department’s lobby was immediately replaced with the institutional hues and cinderblock walls designed for those whose actions caused them to be separated from public life.

“It’s almost like a separate city,” Chapman said. “What you see is that a corrections officer will monitor the population every day, and if he sees a rules violation, he will address it with that inmate.

“It’s no different than an officer on patrol catching someone in the community running a traffic light,” he added.

Through the hallways of the jail, which consist of grey concrete floors, two shades of grey cinderblock walls and grey steel doors, inmates and corrections officers deal with many issues not found outside the chain-link, razor-wired perimeter fence.

Every door inside the jail walls must be opened remotely from one of the jail’s security control and monitoring offices. Every inmate and accompanying officer who temporarily leaves the jail premises, whether trustys completing outdoor labor or suspects attending a court date, must book in and out of the building every day.

Meals are served at the same time each day, prisoners are woken up at the same time each morning and lights are turned off at the same hour 365 days per year.

Because there are several potential security issues with removing an inmate from the jail, the Corrections Division must make every attempt to provide services such as health care in-house.

“The difference between here and the hospital is daylight and dark,” said Roslyn, a former OB/GYN nurse who now works in the jail’s health care wing. “Crack is the cure for everything on the street. A lot of the inmates tell us jail gives them the best health care they’ve ever had.”

Roslyn and fellow nurse, Linda, requested their last names be withheld for safety reasons.

“The main thing in here is that you have to learn how to talk to inmates,” Linda said. “You can’t be mean or rowdy, because they will be mean and rowdy right back at you.”

The importance of separation

At the eastern end of the jail building lies a T-shaped hallway, at the opposite ends of which are two cell block pods containing four separate cell blocks.

The two-story circular pods consist of inmate cells along the outer perimeter and a common area for each cell block. Inmates spend most of their time in the common area watching TV, playing cards and conversing.

The center of each cell block pod contains a guard tower, which is separated from the cell blocks by a circular hallway and tinted glass. Each cell block pod also has a recreation yard, which is a large cinderblock room containing a basketball hoop and capped with steel mesh.

The inmates are separated into three classifications: minimum security, medium security and maximum security, and are segregated by gender. Minimum- and medium-security inmates are housed in the cell block pods, and maximum-security inmates are housed in solitary confinement cells elsewhere in the jail.

Most inmates are medium security, meaning they spend most of their time in the cell block pods or recreation yards. Minimum-security inmates are trustys and maximum-security inmates either committed crimes inside prison or must be separated from other inmates for security reasons.

The prison also has two gang intelligence officers who “stay pretty busy” identifying gang symbols and separating members of known rival gangs, Chapman said.

But even with the jail’s preventative steps, assaults do happen.

“Usually they are no more than two or three punches and then they break it up when an officer comes in,” Chapman said. “They will be over things like ‘he took my Honey Bun.’ It sounds minor, but it’s serious because someone is willing to fight over it.”

The inmates also get “creative” in making and hiding makeshift weapons. When officers conduct unannounced “cell shakedowns,” it is not uncommon for them to find anything from filed toothbrushes to razor blades.

“It’s nothing to find a sharpened toothbrush,” Chapman said, noting it has been about two years since an inmate attacked a corrections officer “with the intent to hurt him.”

Corrections Officer Coley works in the Shelby County Jail's main control station on April 6. (Reporter Photo/Jon Goering)

Video monitors provide a view into the segregation units at the Shelby County Jail. (Reporter Photo/Jon Goering)

The jail business

Shelby County’s jail currently houses a little more than 400 inmates, which is composed of a mixture of arrestees from across the county and federal inmates usually held for the Northern District of Alabama of the U.S. Marshals Service.

Several months ago, the jail housed more than 500 inmates, but funding cuts have caused the jail to reduce its number of federal inmates, Chapman said.

“We are able to control the amount of federal inmates we house, so that number has to go down when our staff is down,” Chapman said. “The county is not getting that revenue from housing all those federal inmates, but we had to prioritize the corrections officers’ safety over revenue.”

Keeping the jail supplied also provides a business opportunity for companies such as American Osment, which sells the jail everything from paper towels to bars of soap.

“The jail is a very good customer,” said Fred Huey, an American Osment distributor. “The amount we sell to the jail varies with the inmate population.”

Because Huey has been supplying the jail for more than 10 years, he said he has come to develop close working relationships with those in charge of the facility, and appreciates the business his company receives from the jail.

“We supply them with a lot of stuff. I will sell them 20 to 25 different types of items every other week,” Huey added. “You can’t help but get to know the people up there you deal with.”