Memory launches Bostick’s career

Published 2:36 pm Friday, April 22, 2011

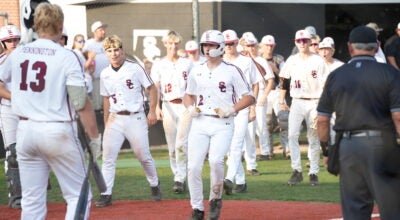

Former Chief Assistant District Attorney Bill Bostick (right), now a Circuit judge, presents former Presiding Circuit Judge Michael Joiner with a parting award during Joiner's fairwell celebration in February. Bostick was appointed April 22 to replace Joiner, who now sits on the state's Court of Criminal Appeals. (Reporter photo/Brad Gaskins)

By BRAD GASKINS / Staff Writer

COLUMBIANA – Shelby County Circuit Judge Bill Bostick easily could have followed in his dad’s footsteps and been a Methodist minister.

He was instead called to another profession as a second-grader, when a phone call in the middle of the night helped chart his future career course.

Bostick, 44, a prosecutor for 18 years, was appointed Friday by Gov. Robert Bentley to succeed Judge Michael Joiner.

Leaving the Shelby County district attorney’s office for the bench was another twist in a legal career that was launched years ago with that phone call to his family’s home in Attalla, Ala.

Bostick’s dad answered the call that Saturday night in the mid-1970s, then left the house in a hurry and his mom crying. It wasn’t until his dad’s sermon the next morning that Bostick learned what had happened.

The church’s youth minister was working at a convenience store when two men arrived to rob it, Bostick recently recalled. The men threw gasoline on the youth minister then lit a match.

Bostick’s dad rode in the back of the ambulance with his fatally burned friend. In the ambulance, the youth minister asked Bostick’s dad to pray for forgiveness for his killers, then died before reaching the hospital.

Listening to his dad’s sermon on forgiveness, Bostick said he could think mostly of one thing: justice.

“Something needs to be done,” Bostick said earlier this week, recalling the event that changed his life.

“My whole life has been oriented to do something,” he added. “It’s not a vigilante thing, but there should be justice.”

And so he pursued it.

Bostick graduated from law school at the University of Alabama in 1992 and married the former Tara Thompson, daughter of retired Marshall County District Attorney Ronald Thompson. Tara Bostick graduated law school a year ahead of Bill Bostick.

“She was equipped for the hardships that come with this,” Bostick said, referring to his job as prosecutor and now judge.

Bill Bostick spent three years with the Mobile County district attorney’s office before leaving for Shelby County.

Bostick served the Shelby County district attorney’s office since 1995 and spent the last nine years as chief assistant district attorney.

District Attorney Robby Owens had been grooming Bostick to succeed him for several years. When Owens’ late wife was stricken with cancer in 2005, Bostick filled in and ran the office. The experience “actually forced me into a leadership role,” Bostick said.

Owens was in the office physically but said earlier this week that his mind was obviously on his wife. Had his wife not died in 2007, Owens said he would have retired already, opening the door for Bostick’s promotion.

Joiner was appointed to the state’s Court of Criminal Appeals in February, and “nobody saw that coming,” Bostick said, calling Joiner a “local treasure” whom he “didn’t feel worthy of replacing.”

Bostick said he reluctantly decided to go through the nomination process at the urging of numerous county leaders. He agreed to do so only after praying things over for more than a week and meeting with Owens.

Bostick tried to work with Owens on a plan to keep Bostick in the district attorney’s office, where he said he really wanted to be.

Then, Bostick said, divine intervention took hold.

“I want to be obedient to whatever God wants,” Bostick said. “It was so obvious that God’s desire for me was to submit to this process.”

Bostick said switching from a prosecutor to judge is – to use a simplistic sports comparison – like going from quarterback to referee. He said he’s up for the challenge, adding that God has “spent my whole life priming me” for the judgeship.

And it all started with that phone call as a second-grader.

Bostick said he doesn’t know what ever happened with that case, or if the youth minister’s killers were ever caught. He’s simply never bothered to check up.

“I’ve got the ability to pull that case,” he said, motioning to his office computer. “I’ve been tempted.”

Either way, that incident left an impression that launched the legal career of the county’s newest Circuit judge.

“Innocence shouldn’t suffer,” Bostick said, “and guilt should not escape.”