Football and forgiveness: Calera’s Bryant-Jordan winner ShaKeith Tyes excels in both

Published 6:21 pm Tuesday, April 14, 2015

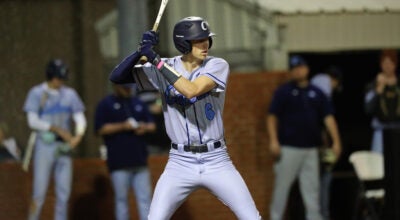

ShaKeith Tyes, left, received the Ken and Betty Joy Blankenship Student Achievement Athlete of the Year Award on April 13 as part of the Bryant-Jordan Student-Athlete Program. (Contributed)

By BAKER ELLIS / Sports Editor

He’s not a big kid.

ShaKeith Tyes stands at about 5-feet-9-inches tall, seemingly undersized for a running back. But the broad shouldered, compact back finished his high school career at Calera High School as the schools’ all-time leader in rushing yards, touchdowns scored, yards per carry and total offense. According to Calera head football coach Wiley McKeller, his career stats make him the 14th most productive running back in Alabama high school history. This by itself is more than enough for any high school athlete to hang their hat on, but in this case, Tyes’ impressiveness extends well beyond the football field.

On April 13, Tyes won the Ken and Betty Joy Blankenship Student Achievement Athlete of the Year Award as part of the Bryant-Jordan Student-Athlete Program. The award recognizes an athlete able to reach extraordinary results in the face of extreme circumstances. He fits the bill quite well.

He has kind eyes and a soft, inviting smile. Whenever his coach starts singing his praises he bashfully lowers his head with that smile playing at the edges of his lips. He is shy and polite, but not to the point of being mute. He has a GPA over 3.0 and has worked extremely hard to keep it there. He’s a volunteer firefighter and a strong Christian. He is a number of things, but at the core he is simply refreshingly genuine.

The story of Tyes’ past has been told in bits and pieces, primarily because that’s the way Tyes relays it. To this day, he attests he is not sure what either his mother or his father did to get routinely incarcerated, all he knows is there was no consistency for him and his three younger siblings in his formative years. His mother would be around, then his father, then neither. Meals were often scarce. The only seemingly consistent element of Tyes’ early life was inconsistency.

When he was 12 or 13, he’s not sure exactly when, he went to live with his uncle, who Tyes attests changed the course of his life and his siblings lives, who has raised him ever since. Tyes found the football field around the same time, and knew early on he had a chance to be special.

“When I first took the practice field, I was pretty nervous,” Tyes said. “I tackled a buddy of mine, I picked him up off the ground and slammed him down. Everybody was telling me, ‘whoa, whoa, you can’t do that’ but the coach came over and said, ‘yes you can do that, that’s football.’ Then I thought, ‘so I am good at this.’”

Through his early years, his parents came to his games whenever they weren’t in trouble. Tyes remembers in middle school his father coming to his games. Every time Tyes broke free and raced downfield for a touchdown, his father always ran beside him, racing him to the end zone. Tyes tells this story with a smile on his face, an obvious sign of a happy memory. Then, his dad began showing up less and less, until Tyes got the news his dad would not be coming to any more games for a while.

The disconnect between the confused, disjointed, often abandoned world this young man was born into and the polished, kind, intentional person he has become is both fascinating and intriguing. He gives his uncle credit for helping him reach his potential. Without his presence in Tyes’ life, Tyes isn’t certain what his life would look like, but he knows he wouldn’t have the grades he has now. Even so, the amount of personal fortitude showed by Tyes in the face of his familial strife is impressive.

“The odds say he shouldn’t be sitting here right now,” McKeller said.

But none of that seems to matter to Tyes. He’s not concerned with the past, or holding on to anger he may have once felt toward his absent parents.

“It’s hard, it’s a hard thing to put it in your head to just let it go,” Tyes said. “But people make mistakes, everyone makes mistakes. You have to think about yourself and the mistakes that you make also.”

This nonchalant thought, and the way he turns the idea back on himself catches me off guard. He is comparing his parents’ abandonment of him and his three younger siblings to his own menial, everyday mistakes. What Tyes means is if he hopes to receive forgiveness for his everyday miscues, it only makes sense to forgive his parents for theirs.

“God put me through a big test to show people when they’re down and out and there’s nothing going for them, that there’s another way,” Tyes said. “There are ways to overcome your obstacles. I tell kids all the time to stay positive in their situations.”

Tyes sees his parents almost every day now, they were at the award ceremony on the 13th, and he will take his talents to Highland Community College in Kansas in the fall, where he will hope to start as a freshman.

He may not be a big kid, but his heart and his ability are larger than life.