PROFILE: From sinner to saint (and everywhere in between)

Published 3:18 pm Tuesday, March 15, 2016

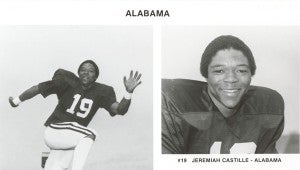

Jeremiah Castille is one of the most recognizable faces in Alabama. The former Crimson Tide cornerback has come a long way from his early days. Here is his story. (For the Reporter / Dawn Harrison)

By BAKER ELLIS / Sports Editor

Jeremiah Castille is a familiar face across the state of Alabama for a couple different reasons. One of those reasons, most assuredly, is football. The former Alabama and NFL star first made a name for himself at Central-Phenix City High School back in the late 1970s, where the then-scrawny defensive back drew attention from the legendary Bear Bryant at Tuscaloosa, who Castille went to play for after he graduated in 1978.

He continued to turn heads and draw attention as the only sophomore starter on Bryant’s 1980 team that throttled Baylor in the Cotton Bowl. When he was drafted by the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in the third round of the 1983 NFL Draft, Castille left Alabama as the career leader in interceptions with 16, a record that stood until 1993.

That’s one side of the Jeremiah Castille narrative. Jeremiah the Football Player. It’s the side most who were around during his playing years will assuredly associate with his name, and rightfully so with the career he had. But there’s more to the man than the game of football.

Much, much more.

Castille is now a 54-year-old father of six. He and his wife, Jean, live in Shelby County and have sent all of their children to Briarwood Christian School, two of whom went on to follow their father and play in the NFL. Castille is a devout Christian who runs the Jeremiah Castille Foundation, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization based out of the Woodlawn area in Birmingham. He still carries himself with an athlete’s gait, and walks with the same lightness and grace that made him so fun to watch on the football field. He has a kind face and thoughtful, intelligent, probing eyes set into narrow sockets on either side of his light brown nose.

However, that face has not always been kind, and those eyes used to be filled with rage, not generosity.

This is his story.

Chaos

Castille was born in 1961 in Columbus, Ga. From as early as he can remember, his house was a breeding ground for alcoholism and domestic violence. His parents had a violent, alcohol-infused relationship with each other, which affected Castille in exactly the way that type of an environment could be expected to affect a child.

“Chaotic is the word for it,” Castille said. “When I say ‘domestic violence’ I’m talking about serious domestic violence from my mom and my dad. You can imagine the trickle-down affect that that’d have on children. I’m talking about every week; alcoholism was the igniter of it. It affects you in a very negative way.”

As a natural byproduct of the violence he was exposed to, Castille was angry from an early age. Violence tends to breed violence, and Castille was the walking embodiment of that reality. He was a surly, confused, emotionally abandoned kid who was in danger of failing out of school before he turned 15 because he just didn’t care. It was precisely through this anger and consternation that Castille believes God worked to radically change his life.

Castille got suspended from school when he was 13 for fighting. An eighth grade basketball player tried to jump in front of him in the school bus line, and Castille was having none of that. The two fought, and a suspension ensued. It was not the suspension by itself that caused Castille to reexamine his life. Fights were common, and school was not important to him. It was when he took the suspension letter home.

“When I took the suspension letter home, my mother had to sign it,” Castille recalled. “And when I gave it to her it was a day she was sober. And my mother said something, she said, ‘Son, I’m so disappointed in you.’ And man, I’m telling you, for whatever reason, that touched my heart.”

Castille has a two-inch scar running across his left forearm to this day from where his mother pulled a knife on him in a drunken rage and cut him when he was 11. When he said the violence he saw and endured as a child was serious, he wasn’t exaggerating. If there was anyone who ever had good reason to not care whether or not their mother was disappointed in them, it was a young Jeremiah Castille. But something about that moment of disappointment, as a 13-year-old, touched him.

“What I’ve learned from this is that God puts in every teenager a desire to please their parents,” Castille said.

In that moment of clarity, a 13-year-old Castille knew he had to make a change.

Jeremiah Castille prays with former Florida State University head football coach Bobby Bowdon. (Contributed)

Faith and Football

Castille did not grow up going to church. His father had grown up Catholic but religion played essentially no role in his early upbringing. That summer however, the summer before his eighth grade year, his life changed while serving his suspension from summer school. He attended a revival at Pleasant Grove Baptist Church, which is where he found what he didn’t even realize he had been looking for.

“I heard the Gospel for the first time,” he said simply of that experience. “I heard, for the first time, that God loved me. That’s what I had not experienced. I had not experienced a human love. Even though there was shelter for me, I had never experienced a father-son love or a mother-son love, I hadn’t experienced that.”

It was this moment of realization and acceptance, even all these years later, that Castille points to as the defining moment in his life. He couldn’t get enough of this new concept of redeeming love. He had been searching for a vessel to fill a yawning gap in his life that he couldn’t even fully describe, and had finally found it.

“When that was communicated to me, man I jumped right on it,” Castille said with a smile. “I left that church a different person. I went in a sinner and came out a saint. The power of the gospel was resonant in me. I left there empowered.”

As Castille was being given the gift of spiritual renewal, he also began to realize he was gifted in other ways as well. He began to play football his eighth-grade year, and quickly developed into one of the state’s brightest young stars.

There was never any doubt in Castille’s mind where he wanted to play college ball. It was Tuscaloosa or bust for the young, gifted defensive back. Even now, 30-some-odd years later, Castille still vividly remembers the first time he got a letter from the Crimson Tide. It was his junior year in high school, after the season was over. He was in the cafeteria and his positions coach brought him a letter from Alabama expressing interest in him.

“I was sitting in the lunchroom, and my position coach brought me the letter. I started reading the letter and I jumped up and ran out of the cafeteria yelling,” Castille said, laughing. “It wasn’t even offering me a scholarship, it was just saying they were interested in me.”

That letter took Castille’s work ethic to another level, and after a stellar senior high school season, he was off to Tuscaloosa.

Alabama, The Bear and the NFL

As a freshman, roughly two weeks into his tenure as a member of the Crimson Tide, Castille had an encounter that shaped the rest of his football career. The most prolific and esteemed college football coach in the country, Bear Bryant himself, had requested an individual meeting with the young, skinny defensive back.

A nervous, homesick, 18-year-old Castille made the trek across campus to Bryant’s office in Coleman Coliseum, where Bryant was waiting for him, Chesterfield cigarette in hand, to talk to his newest protégé. Castille walked into the hazy office and sat on the black and white checkered couch Bryant kept in his office, and immediately sunk to the floor.

“That couch doesn’t have any springs by design,” Castille said with a grin creeping on to his face, reliving the moment in vivid detail. “He took the springs out of the couch, so when you sit on the couch your butt’s on the floor and you’re looking up at him.”

Bryant looked at Castille, right in the eye, and told him in his gravelly, matter-of-fact voice that he could play for the University of Alabama. Not in two years, but right then. Bryant had seen enough out of the 155-pounder to know Castille had what it took to play on the national level.

“He could see what a guy had. Whether or not you had what it took,” Castille said. “He was also the most encouraging coach I ever had. I left that meeting and he said, ‘Jeremiah you see that door? If you ever need anything, that’s always open to you.’ I left there feeling like someone cared about me.”

Looking back at his record setting career in a crimson jersey, Castille points to that moment, that meeting on a sunken couch in a cigarette-smoke-filled office, as the catalyst the propelled him to have the career he had.

Castille graduated from Alabama in 1982 and was drafted in the third round of the NFL draft by the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Bryant died soon after Castille left Tuscaloosa, in January of 1983. At the funeral for the legendary man and coach, Castille was one of the eight pallbearers that led Bryant to his final resting place.

Castille’s eyes are kind and give insight into his demeanor towards others. (For the Reporter / Dawn Harrison)

All-Encompassing Ministry

Castille spent six seasons as a pro. He was in Tampa Bay for four years before being traded to the Denver Broncos, where he helped lead the Broncos to Super Bowl XXII with his play in the AFC Championship Game against the Cleveland Browns. He recorded 14 interceptions in six years, including seven in the 1985 season. But, after just six seasons, Castille felt he was being called away from the game that the world had come to associate him with.

He felt he was being called away to start something new, which was one of the hardest decisions he has had to make. He had agreed to a contract with the San Francisco 49ers after being released by the Broncos, but felt the Lord call him away from the game.

“There was a battle between He and I,” Castille said. “Internally there was a struggle. I’m a very competitive person and wanted to keep playing. In that process, the Lord stripped me of all that competitiveness.”

He felt called to continue ministering in other ways, and has done just that since his playing days. He coached at Briarwood for seven years where his children went, and at the same time started the Jeremiah Castille Foundation, which incorporated in 1999. He stepped down from his coaching position in 2001 to be the team chaplain at his alma mater, Alabama, a position he still holds today.

That’s the pattern for Castille’s life. Transition is easier for him than most because he views whatever he is doing in any given moment through the lens of ministry. Playing football, coaching, running an outreach program, it doesn’t matter. The act itself is significant only in light of the ministry opportunities it brings. And the opportunities have been plentiful.

Blessing those around him

Castille’s mom is 30 years sober now. She still lives in Central-Phenix City and is actually is in one of the videos on the Jeremiah Castille Foundation website with her son.

His children are old and grown. Caleb, the youngest son, recently starred in the independent film Woodlawn while Tim is now coaching football at Thompson High School.

The Foundation has been running in the Woodlawn area of Birmingham since it incorporated 17 years ago. The Foundation is partnered with Cornerstone Schools of Alabama in Birmingham and is in the process of developing property in that area of Woodlawn. It has not been uncommon for Jeremiah and his wife, Jean, to welcome wayward youth into their home for months at a time to help them get through school or nail down an elusive job.

There is no way to quantify how many lives the Jeremiah Castille Foundation or the man responsible for its inception has already helped to change. But the man who is the foundation’s namesake has no plans to stop his work soon.

Through it all, what is most impressive about Castille is not in the ways he has been touched and blessed on the field, but in the ways he has been able to touch and bless those around him off of it.