Mill memories live on

Published 4:24 pm Monday, August 14, 2017

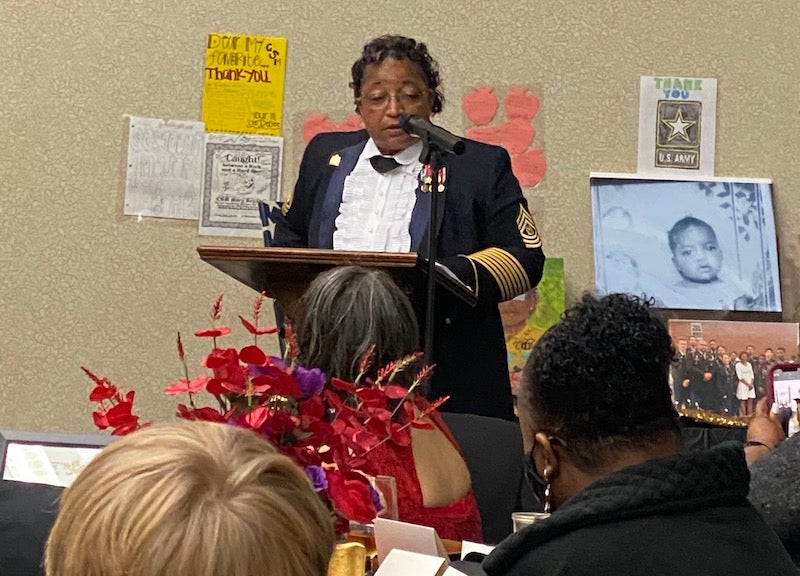

- Workers at Siluria's Buck Creek Cotton Mill pose for group portrait circa 1917-1921. (Contributed)

By RENE’ DAY / Community Columnist

For most of my growing up years, I thought my grandmother had the only copy of a photograph showing a large group of male and female workers standing proudly in front of a large, impressive brick building with rows of windows and a central tower. The men are mostly wearing overalls and white shirts; the women dressed in light, white cotton dresses that, it appeared to me, indicated the photo was taken in the spring or summer. It was fun to see if we could find a young Nannie Mae Lightsey among the girls grouped together in the right center of the picture. More often than not, we were wrong in our guesses. For some odd reason, we never wrote down her location on the back. I assume we thought she would always be around to point out her much, much younger self.

Anyone having had Alabama history at some point in their education is sure to know that Shelby County holds a prominent place in the industrial development of Alabama. Across it runs the Cahaba coalfield that hosted mining operations in towns like Aldrich and Helena. These “diamonds in the rough” supplied fuel for iron smelting at the Brierfield and Tannehill furnaces in neighboring Bibb and Tuscaloosa counties. Its plentiful rivers helped development of other industries including lumber milling and textile manufacturing.

In fact, textile production is what brought my grandmother’s family to Siluria, Alabama, around 1917. Situated on the banks of the creek was Mr. Thomas C. Thompson’s Buck Creek Cotton Mill, founded in 1896. Poor crop yields for several years forced share-croppers like the Lightseys from their tenant farms in Chilton County to the relative “comfort” of the houses built by Mr. Thompson in his “model” mill village. Here, the entire family could find work. Nannie, only 11 years old at the time, could earn 10 cents an hour for each of the eleven hours she worked. Lack of child labor laws meant she could add $1.10 a day to the family income. They lived in company housing, shopped at the company store and worshipped in the mill village church. Even though other children often called them “lint heads” because of the inability to remove all of the fine fibers that covered everything and everyone in the mill, she said her time there was among the happiest of her life.

Today, the mill is no longer there. The only reminder is the old water tower that stands guard over the new Alabaster Civic Complex. However, the memory of Buck Creek is far from forgotten. Each year, people whose lives were shaped by this place meet to swap stories, photos and memories. This year is no different. As I write, former employees, families, and friends are planning the annual Buck Creek Mill Reunion. It is one small way in which they keep this part of history alive. My mother and I will be there, with our copy of the photograph. I think Nannie would be pleased.