PROFILE: A difference maker: OMMS Principal Sandy Evers reflects on her path

Published 11:11 am Wednesday, March 13, 2024

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By DONALD MOTTERN | Staff Writer

On the afternoon of Feb. 12, 2013 Chelsea Middle School was experiencing the regularly-scheduled chaos of a normal school dismissal. As was the policy at the time, hundreds of middle school bus riders poured into the school’s gym where they prepared for bus dismissal. Sandy Evers, who had just finished her last class of the day in her position as a P.E. teacher, stood attentively and watched over the procession of students while she waited for another adult to take her place for dismissal duty. In those seconds, watching students cascade in, she never anticipated the words she was about to hear next.

In the midst of the organized bedlam, one sixth-grade girl ran toward Evers as the words left her lips, “Coach Evers, coach Evers, there’s a man in the locker room with a gun.”

“It’s one of those moments, one of those powerful moments in your life where time stands still for a second,” Evers says, looking back on the event from 10 years ago. “It catches your breath and you almost want to turn back time, but you’re standing right there and you can’t. I vividly remember repeating in my mind, ‘What did she just say? Did she say what I think she just said?’”

The words sank in quickly, however, and Evers, who has always described herself as quick to react, took those few words with the seriousness and weight that they deserved. In the next seconds, she was already speeding down toward the locker rooms, which were on the floor below the gym. Already bolting in that direction, she yelled into her school radio, “Code red, put the school on lockdown,” but heard no response, finding out later that there was a technical problem with the radio leading to no alarm sounding.

As a P.E. teacher, and a cross country and track coach, Evers was perfectly aware that with the school day concluding, girls would be steadily making their way to the locker room to change and prepare for the many different after-school sports and activities.

“When I got to the bottom platform there was this long singular narrow hallway and there’s two entrance doors that lead into the girl’s locker room,” Evers remembers. “I saw that the door was open and all I could see was an arm in a camo-like jacket with a gun—and the gun was pointed at four of my sixth-grade girls.”

Evers quickly reached the end of the hall and threw herself into the room and in-between the man and her students. Already a mother of four children, Evers thought only of protecting those in her care.

“I just ran to the girls and just grabbed at four of them and just threw them toward the stairs where I just came from and just yelled for them to run,” she said. “Meanwhile, I never even looked at him, I could just feel that he was still behind me with a gun now pointed at the back of my head instead.”

Answering an unexpected calling

Evers hadn’t anticipated a career in education. In college, she ran track at the University of Kansas and was a heptathlon competitor. Before a pivotal moment changed that trajectory forever, she fully believed she would find herself going into personal training or corporate fitness.

With her father having passed away from a heart attack the year prior, Evers was preparing to compete in her Big-8 Track Championship held in Ames, Iowa. As she prepared for her event, she heard a familiar voice from the crowd cheering her on, Dr. Byrle Kynerd.

Kynerd, who was the superintendent of Briarwood Christian School where Evers had attended five years prior, had traveled across the country at the closing of a school year to see her compete and cheer her on. Knowing Evers’ father wasn’t able to cheer her on, he had made the trip to let her know that he was proud of her. It was this simplest of gestures, appearing at a competition, that changed the course of Evers’ life forever.

“When he came out to watch me compete, he asked me to please consider coming back to Briarwood and teaching and coaching and getting my teaching certificate,” Evers recalled. “He changed my life, for the better. Him believing in me and thinking that I could make a difference in young people just as he made a difference in my life, it was amazing.”

From that moment, Evers knew that she wanted to do for others what Kynerd had done for her—be a difference maker in the lives of others.

She returned to Briarwood in 1995 where she began coaching and teaching, a position she maintained for years until spending one year at Bessemer City High School and then making the move to Chelsea Middle School in 2010. Less than three years later, she stood in the girl’s locker room with a gun pointed toward the back of her head seconds after throwing four girls out of the way.

“The girls took off running, they were obviously scared to death,” Evers said. “God was watching out for me that day and it was not my time either. At that moment, the gunman instead made the choice to go (further) into the locker room and retreated that way instead of doing anything with me.”

Evers never made direct eye or verbal contact with the gunman, instead, she kept moving. Just seconds had passed since she first ran down the stairs, and girls were still coming down the stairs unaware of the seriousness of the quickly developing situation. Not yet knowing what was going on deeper in the locker room, Evers moved to clear the area and get as many out of harm’s way as possible.

“I just yelled to them, ‘run, run, run,’” she said. “They were just coming down there to get dressed for spring sports. I’m yelling at them, ‘Go back upstairs, go, go.’ I was trying to be quiet, because I didn’t want (the gunman) to hear. It felt like forever, but it’s all happening in split seconds.”

As students in the hall and stairwell ran back to the gym, Evers again turned her attention back to the locker room, peering into the second entrance, and finding no one in the immediate area.

“I’ve yelled on the radio and at this point I peak into the room and open the door to see if I can see any girls—if I can get anybody else out and all I could see was lockers,” Evers said. “I could hear him yelling in there but I couldn’t see any girls, I couldn’t see anybody at that point.”

Still, students continued arriving and heading down the stairs, and Evers, unaware that her radio call was not received, began to fear that the school was under a larger scale attack with more than one assailant. Still fearing for the safety of any students in the locker room, she made the decision to quickly make her way upstairs and ensure that no students could make their way downstairs.

Once making her way back up to the gym, Evers was face to face with 350 students that were still unaware of the emergency unfolding below them, she ran to the microphone on the gym’s stage and again declared that the school was in a code red situation. Following that announcement, the reaction swiftly escalated and the school’s crisis response plan kicked into full gear.

Evers remained by the door to that stairwell during the entire incident, placing herself between her students and whatever might be on the other side. As she did so, Shelby County Sheriff’s Office Deputy David Morrow, the school resource officer on duty that day, and the school’s principal, Bill Harper, made their way to the locker room and were further directed by a custodian who had also been downstairs during the incident.

“I knocked on the door and yelled ‘Sheriff’s Office,’” Morrow said. “I opened the door, and when I did the offender came around the corner. He started yelling, ‘Get out of here, get out of here.’ And I was yelling, ‘Sheriff’s office.’ He and I saw each other. I saw the gun in his hand. I began giving him commands to drop the gun. He did not drop the gun. He lowered the gun and immediately ran back away from the door against the wall where I couldn’t see him.”

Not wasting any time, Morrow immediately called for backup and entered into negotiations with the man and it was then that he heard him say he had five young girls hostage in the room with him. Over the next several minutes, and as more officers arrived, the identity of the gunman became clear, especially to Principal Harper.

“Talking to the guy through the door, he recognized me as being his former SRO when I was at high school,” Morrow remembers. “And the principal knew him, recognized him because he had worked as a custodian, as a as a summer helper. I didn’t recognize him, but he knew who I was. The relationship that the principal had with him, for a couple of summers, (played a crucial role). We were able to talk to him and he immediately released three of the girls.”

Over another tense few minutes, Morrow, Harper and other officers were able to talk to the gunman and were able to successfully talk him into standing down. In the years that followed, it was determined that the gunman was suffering from mental illness. He was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and placed under the custody of the Alabama Department of Mental Health in 2014.

“My belief is that the relationship that he had built with the principal and that he knew me as his former SRO when he was in high school, played a big role in everything that took place and the peaceful outcome that happened that day,” Morrow said. “And that’s what we do as SROs, we try to build those relationships with these kids and let them know that we’re there for them.”

As Evers stood at the top of the stairs, she had no idea that she too had known the man responsible for the last half hour of terror. Throughout the entire event, Evers never saw his face, but looking back now, she easily recalls how he helped her put together furniture for her office prior to the incident.

“(Evers) did exactly what she was supposed to do,” Morrow said. “She got those kids out of the way—the ones that were up in the gym—she did absolutely fantastic by keeping those kids out of there and keeping them contained upstairs and away from the danger.”

Making the difference

It is an unfortunate fact that this event and others across the country have resulted in learning experiences that have led to the design of new safety systems and protocols in schools. In part due to her involvement on Feb. 12, Evers played a role in the reevaluation of safety policies and procedures as a member of the district safety team that was organized shortly after the events.

“It was a healing process to be quite honest, but it also was a learning process for our county to be able to move forward and better prepare our school system, kids and our community to be safer,” Evers said. “I was in shock for a little while—I don’t think I realized that’s what it was, but it was surreal to me. I didn’t realize that sudden loud noises affected me the way they did for a little while. I will say, I tend to be resilient and positive, I look for the good in things. That’s been the life motto of mine, to look for the good and find the good in things.”

Finishing out the remainder of that school year at ChMS, Evers made a move to teach PE at Forest Oaks Elementary the following school year. During her time there, she attained her administrator’s certification and eventually moved to serve as the head assistant principal of Oak Mountain High School for seven years.

“Sandy and I worked together for two years and she was really my right-hand woman,” says Principal Andrew Gunn of Oak Mountain High School. “I relied on her for so much and she was an absolute joy to work with.”

Gunn worked with Evers for the last two years of her time at OMHS, having also worked at ChMS but starting the year after Evers’ departure.

“She truly, truly cares about the students and their wellbeing,” Gunn says. “She is very much a student first person. When it comes time to make a difficult decision, she is going to decide and make her decision based on what is best for the students. She is a very joyful person and she knows every kid personally as much as she possibly can and gets to know them. They know that she cares for them and has their wellbeing in mind.”

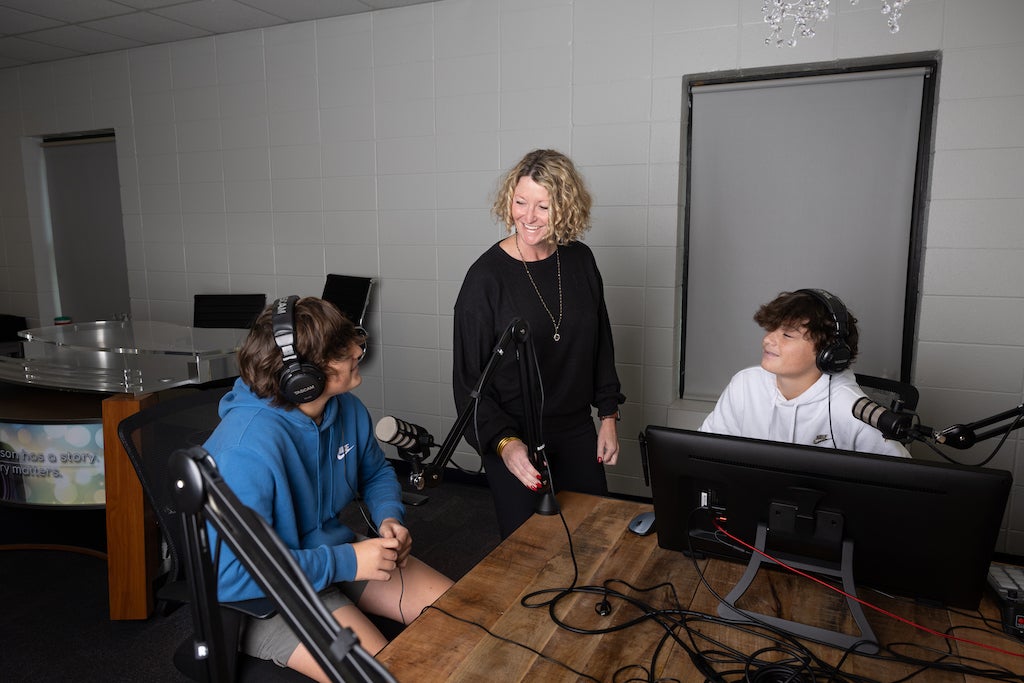

That energy Evers has always carried and brought to every position now resides in the halls of Oak Mountain Middle School. This past July, Evers made one last move to become the principal of OMMS, filling the position following the retirement of Larry Haynes after nearly 20 years in the position.

Here, now nearing 11 years since the event in February, 2013, Evers walks up and down the halls conversing and greeting students, many by name in the moments prior to dismissal. The process is much different now than it was then. Most students have been dispersed to their advisory classes and retrieved their belongings and backpacks from their lockers. A select number of students carry dusters, dustpans and brooms as they clean the halls before dismissal, and they call out for her attention from down the length of the hall. With each and every student she encounters in the hall, she stops to talk and check in with them in a way that is clearly so much more than a general comment.

“I love middle school kids, I love that age,” she says as she waves to several students down the hall. “It is such a pivotal time in a young person’s life and I love that I’m able to be here during that transformational time in a young person’s mind—where they’re deciding who they’re going to be and making those choices. I love that I can be that extra voice for them encouraging them to do the right thing and make the right choices—to encourage each other, build each other up and say nice things.”

On the right path

Before Evers’ alarm, which reminds her to make the afternoon announcements, goes off, she stops in to speak and visit with the students of a special needs classroom. There, she is bombarded with greetings and smiles and she takes a moment with each student to ask about their day. Although a short moment that is over quickly, any observer can see that it is easily the part of the job Evers loves the most. As she leaves that class and walks down the hall, posters and writings can be seen that proclaim the words that enshrine her teaching philosophy, work hard, be nice, smile and call home.

In an image that may be foreign to some, not one student across the entire campus seems anything but ecstatic to see their principal.

Promptly, at 2:53 p.m., Evers is back in the office and reading the afternoon announcements, and as she concludes she dismisses the students. Over the course of the next 10 minutes, 42 buses, carrying more than 800 students, leave the OMMS campus through one exit. Roughly another 400 wait in the car rider lines. Every radio works and administrators confirm and double check with each step of the process. It is a surprisingly organized chaos that sees a school go from buzzing with activity to silent in minutes.

By 3:07, just 14 minutes after Evers first began her afternoon announcements, the entire procession is over. Every bus is on time, and every student gets where they need to go. All in all, the process is six minutes shorter than the entire length of the incident in 2013.

For Sandy Evers, it’s just another day where she has been able to make the difference, something she has loved doing for the past 27 years and intends to do for years to come.

“I think as many adults in their world that can encourage them and help them stay on the right path the better,” Evers says. “I am in a great place. Oak Mountain Middle School is amazing. The students, community and parents are amazing and it is a blessing and a joy to be here. I cannot say enough great things about it, it’s been great.”